TSMC and Samsung seem destined to claim the throne for themselves, but Intel still feels it can catch up. How many leading-edge semiconductor manufacturers will be left standing at the end of this decade?

Semiconductors have always made for an exciting industry. The cutting-edge R&D fueling innovation at a back-breaking pace, the enormous upfront investments and the brutal competition make for a game that’s thoroughly enjoyable to watch. At the leading edge, the stakes have never been higher than they’re right now, though.

The investment and operational excellence required to implement the most advanced process technologies for logic devices has driven out all but three companies from the semiconductor’s Premier League. The multibillion-dollar question is how many players will still be left standing at the end of this decade.

Having obtained technological leadership and, according to one estimate, already manufacturing 92 percent of the world’s leading-edge foundry chips, TSMC’s future seems secure. Samsung should be able to hang on, but Intel has a mountain to climb.

Destined

Right now, Samsung is TSMC’s only competitor for contract manufacturing of leading-edge chips. The Korean company started to offer foundry services in the mid-2000s, as it realized that only the largest chipmakers will survive in the long term. Despite an unprecedented spending spree over the past few years, however, it hasn’t managed to close the gap with TSMC. Technologically, the Koreans are not that far behind the Taiwanese, but the latter’s market share across all nodes is more than three times higher (55 percent versus 17 percent in 2020), according to data from Trendforce.

But Samsung isn’t a pure-play foundry. In fact, it’s more like an IDM: most of the chips it manufactures end up in smartphones, TVs and other electronic devices of its own making. This limits the potential of Samsung’s foundry business because many companies don’t like handing over their designs to a competitor for manufacturing. On the flip side, Samsung’s chip division is always assured of orders from some of the biggest chip-buying customers in the world: the other divisions of the chaebol.

As long as Samsung manages to stay reasonably close to TSMC, it should be able to continue to operate at the leading edge. If it falls too far behind in process technology and manufacturing capacity, competitors in end markets would gain too much of a competitive edge. Longer-term, keeping up in scale will be a challenge.

According to market research firm IC Insights, TSMC and Samsung are all but destined to claim the leading edge for themselves, since no other company will be able to match – let alone top – their spending. TSMC plans to invest 100 billion dollars in R&D and manufacturing capacity expansion over the next three years. Samsung recently pledged 150 billion dollars by 2030 – and that number doesn’t include investments in its already-dominant memory business.

“With no other companies presently able to match these huge spending sums, Samsung and TSMC will likely put even more distance between themselves and their competition this year with regard to advanced IC manufacturing technology,” IC Insights concludes. “Samsung and TSMC are well on their way to world domination of leading-edge IC process technology, the cornerstone of all of the advanced consumer, business and military electronic systems of the future.”

Stack up

Intel feels it can still join the Asian duo, though that’s clearly going to be a tall order. After Intel gave away what was once a comfortable technology lead, TSMC customer AMD has already been making big inroads into Intel’s market share. Adding insult to injury, the once X86-dominated leading-edge semiconductor landscape has become a much more varied ecosystem. Arm, GPU and other architectures are slowly encroaching on Intel’s bread and butter.

The former king of the hill has responded with an ambitious counter-offensive. First, it has vowed to close the gap with its Asian competitors. According to CEO Pat Gelsinger, his company will return to the famous tick-tock model of alternating process node enhancements with architectural improvements in a yearly cadence (two years per cycle). Along with innovative packaging solutions, Intel is looking to regain “unquestioned CPU leadership performance” by 2024 or 2025.

It’s difficult to put that target into perspective, since leading-edge chip manufacturers increasingly make different technology choices. Intel currently plans to start volume production of 7nm chips by late 2022 or early 2023. TSMC’s 3nm node is scheduled to enter volume production in the second half of 2022 and expected to be superior to Intel’s 7nm. It’s estimated to be 1.5 times as dense, for example. Still, Intel may be able to compete on specific characteristics, such as CPU performance.

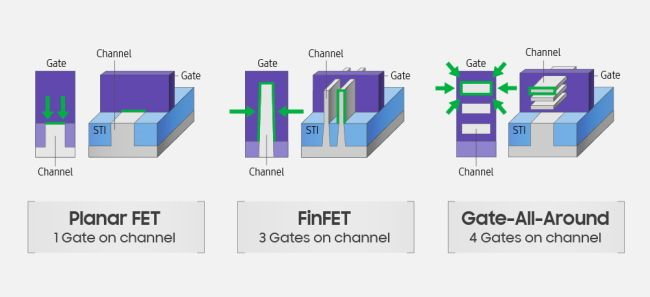

Samsung, too, will begin churning out 3nm chips somewhere in 2022. Unlike Intel and TSMC, however, the Koreans will transition from FinFETs to nanosheet gate all-around transistors (GAA). FinFET gates are draped over raised current channels on three sides, whereas GAA gates envelop them completely to more effectively cut off the flow of electrons. Again, it’s hard to tell how Samsung’s 3nm GAAs chips will stack up against TSMC’s 3nm or Intel’s 7nm FinFETs. TSMC plans to introduce GAA at the 2nm node, and Intel is also working on it, though it’s unknown when it plans to implement it.

Mix-and-match

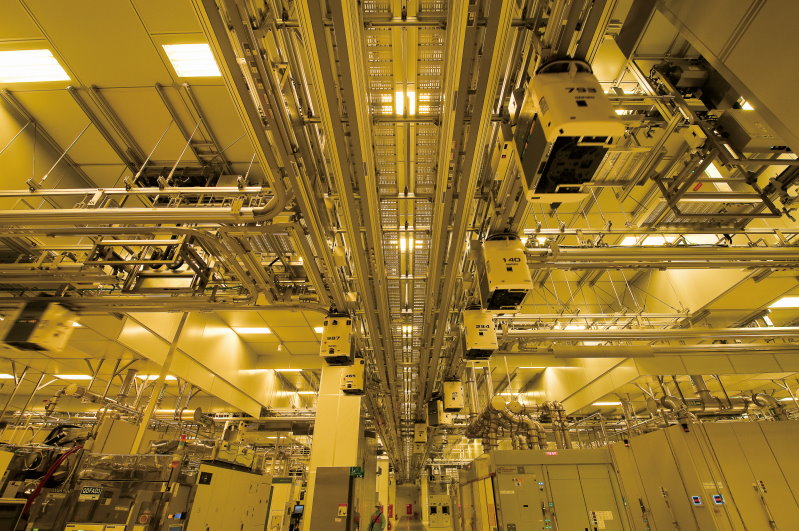

The second pillar of Intel’s counterattack is to embrace the foundry business model once again, after a half-hearted attempt in the last decade failed. This is partly an opportunistic move, playing on Western anxieties brought about by the current global chip shortage and by the fact that leading-edge manufacturing is essentially concentrated on an island claimed by China as its territory. Gelsinger keeps stressing that the chip shortage will take years to resolve, and kindly offers to build new fabs so the West can feel more secure about its chip supply. He does require governments to lend a helping hand, of course.

By contrast, TSMC chairman Mark Lin says that the reasons for the shortage are more to do with imbalances and uncertainty in the supply chain and not the lack of capacity itself. Clearly, though, TSMC believes demand will grow, otherwise it wouldn’t be spending record amounts over the next three years.

Moving into the foundry business is also a strategic step for Intel, allowing it to manufacture chips for markets it currently doesn’t serve. If Intel would stick with only manufacturing its own products, it won’t have the scale required to keep up with TSMC and Samsung. Like Samsung, however, Intel competes with some of its potential customers.

Somewhat confusingly, Intel will also outsource manufacturing to third-party foundries, including advanced devices. This has drawn scorn, painting a picture in which Intel wants to make chips for others it can’t even make for itself. In reality, developments in packaging render things more nuanced.

Intel is preparing to move from monolithically integrated systems-on-a-chip to systems-in-package in which different dies (compute, memory, I/O and so on) are stitched together. These dies are manufactured using process technologies that best match the associated function after weighing cost, performance and power efficiency.

This mix-and-match approach has a number of intrinsic advantages. For some parts of a processor (such as the I/O circuitry), scaling is no longer beneficial in terms of performance or power use. It’s therefore more economical to focus design efforts on those parts of the chip that do benefit from a shrink. Other benefits include increased effective die area, better yields and reuse of chiplets in multiple products. That’s why all leading-edge chipmakers are working on it.

For a company in Intel’s position, the ability to flexibly combine different production processes, whether from its own fabs or outside foundries, is particularly advantageous. Having fallen behind, this way it can still access best-in-class technology without having to outsource production of the entire chip, which would most likely lock Intel into a single process at a single foundry.

Eerily

All in all, Intel has quite the to-do list. Make up ground technologically, build fabs and keep them filled, successfully adopt a foundry mindset this time around, get customers to sign up, stay competitive and keep shareholders happy. It doesn’t necessarily have to offer foundry services from the leading edge from the get-go, though. It might choose to join the foundry party with its very mature 14nm process first and work from there. Either way, it will require flawless execution – a traditional strength of Intel that has taken a severe battering lately – to catch up.

Given the exuberant spending of Samsung and TSMC, Intel will probably require generous government support. Both the US and European countries have been taking another good look at their chip supply chain and are now quite eager to support semiconductor manufacturing, but they don’t seem to realize how much will actually be needed. IC Insights estimates that governments will need to spend at least 30 billion dollars per year for a minimum of five years to have any reasonable chance of success. So the 52-billion-dollar shot in the arm for the US semiconductor industry, recently approved by the US Congress, doesn’t qualify as anything more than a decent start.

Over all this looms the question: can the world even afford for Intel to drop out of the race, leaving us with only two leading-edge chip manufacturers? Two is eerily close to one. Do we really want to move in that direction?